The Financial Times had a story last week about a leaked internal Nestle presentation, which said that less than 40% of the company’s food and drink portfolio, by revenues, met health standards. (I’ve linked it here via a less-paywalled version re-published in the Irish Times).

Health standards were defined as exceeding 3.5 on the Australian 5-star system, regarded as an international reference point.

Under-performing

Overall, the food and drink businesses represent about half of Nestle’s overall £72 billion turnover. These are not small numbers. By product, around 70% of Nestlé’s food products failed to meet the threshold. Some of the individual products mentioned in the report–such as some versions of Nesquik–have shocking sugar or sodium levels.

As the presentation puts it, “our portfolio still underperforms against external definitions of health in a landscape where regulatory pressure and consumer demands are skyrocketing.”

Regulators

This reminds me of one of the six themes in our recent urban food futures report (pdf), blogged about here yesterday. We summarised one of our six themes, ‘Health in the chain’, like this:

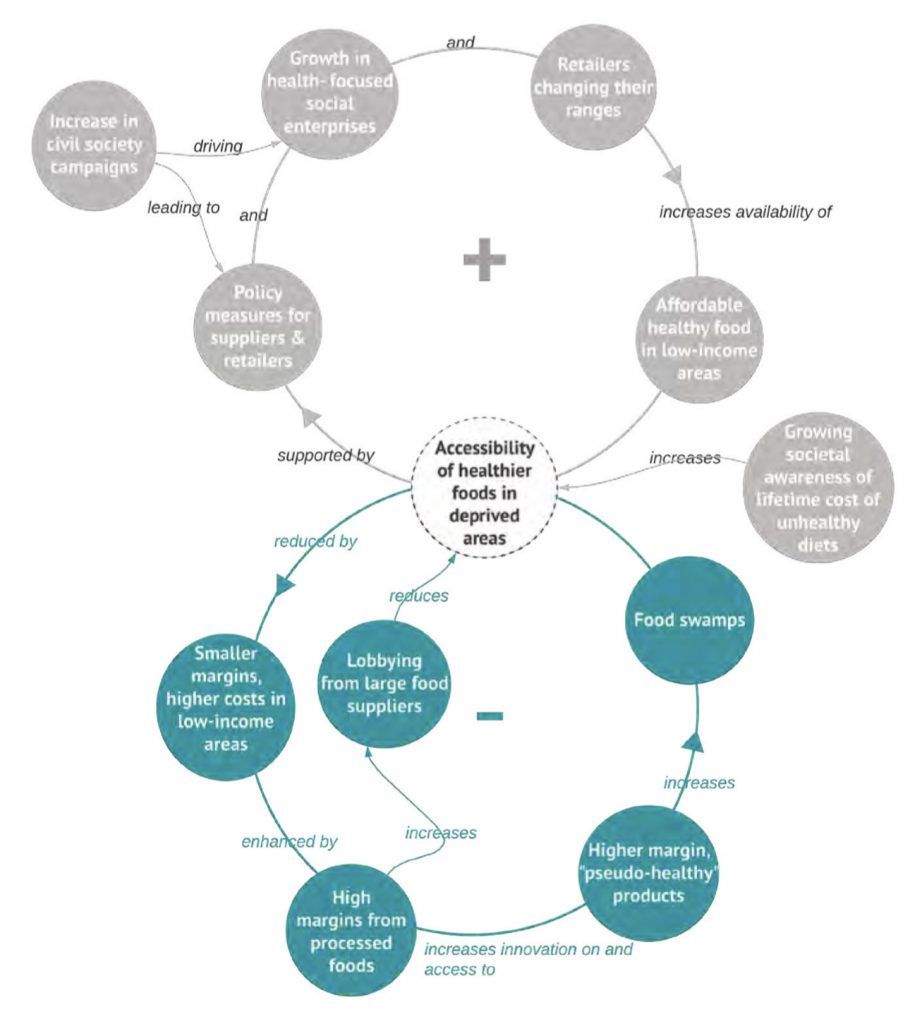

As awareness of the lifetime costs of unhealthy diets rises, will regulators and businesses work together to increase access to healthier options in lower income areas? Or will corporate lobbying protect food deserts from regulation?

We analysed this through a set of causal loops, which are included as an appendix to the report.

Reading the article through the lens of the causal loops diagram, it captures both the positive and negative loops.

Slow work

On the one hand, Nestle is, apparently, working to update its internal nutritional standards. On the other, it’s also thinking of moving some of its categories outside of the standards—for example some of its confectionery products.

At the same time the Chief Executive is not persuaded that “processed” foods are unhealthy per se.

The fact is that it’s slow work to improve the health profile of processed foods. But it’s not impossible. The companies in the sector that are applying themselves to it tend to have better share value growth profiles and are able to attract higher quality recruits.

A longer version of this post also appeared here. To find out more about our work on the future of urban food, please talk to Andrew Curry or Emma Bennett.