In a recent SOIF training, I shared some reflections on methods for getting decision-makers to inhabit futures work. Andrew Curry often likens this work to Narnia–where you have a rich, otherworldly exploration but can struggle to make people believe it when you step back through the wardrobe.

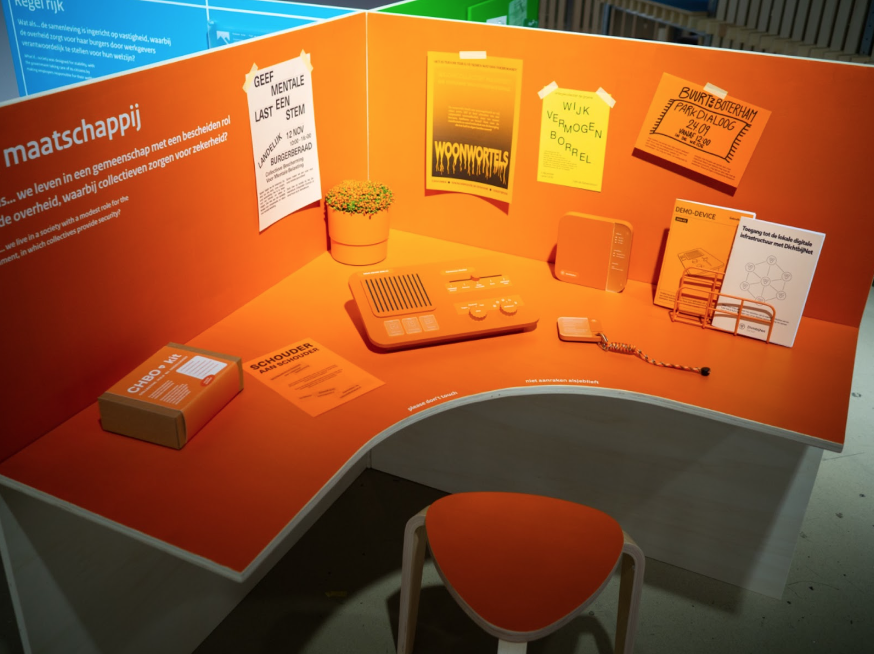

Alongside SOIF, I co-lead an experiential futures practice called ‘Futurall’. Last weekend, we launched an experiential futures exhibit at the Dutch Design Week that looks to do just this—for members of the public and policymakers. The exhibit featured four future desks, bringing to life stories of different kinds of workforce rights and instabilities. When you sit at the desks you step into their lives, rustling through their post, reading their calendars, signing their contracts and interacting with fictional gadgets that support certain freedoms at uncertain costs. It gets personal fast.

Drawing on this project, and others, here are some learnings from my experiential futures practice:

Start small. The first response from civil servants to this kind of work is, “we don’t have the budget for that.” But Stuart Candy and Kelly Kornet show that experiential futures are best served in cycles. Start with simple artefacts like a letter, postcard, or voice recording (…by a professional voice actor on Fiverr?). Evocative artefacts, however small, breed interest and engagement, and larger projects might well follow.

Policy makers are like Shrek. They have layers—and experiences can have layers, too. Senior officials will need the 3 minute ‘sound bite’ experience, but others will have more time. The future-of-work exhibit has been designed to be eventually installed somewhere in the Ministry’s foyer. Across the range of objects on each desk, some reveal their truths more slowly, but every desk has at least one artefact that tells the story short and sharp.

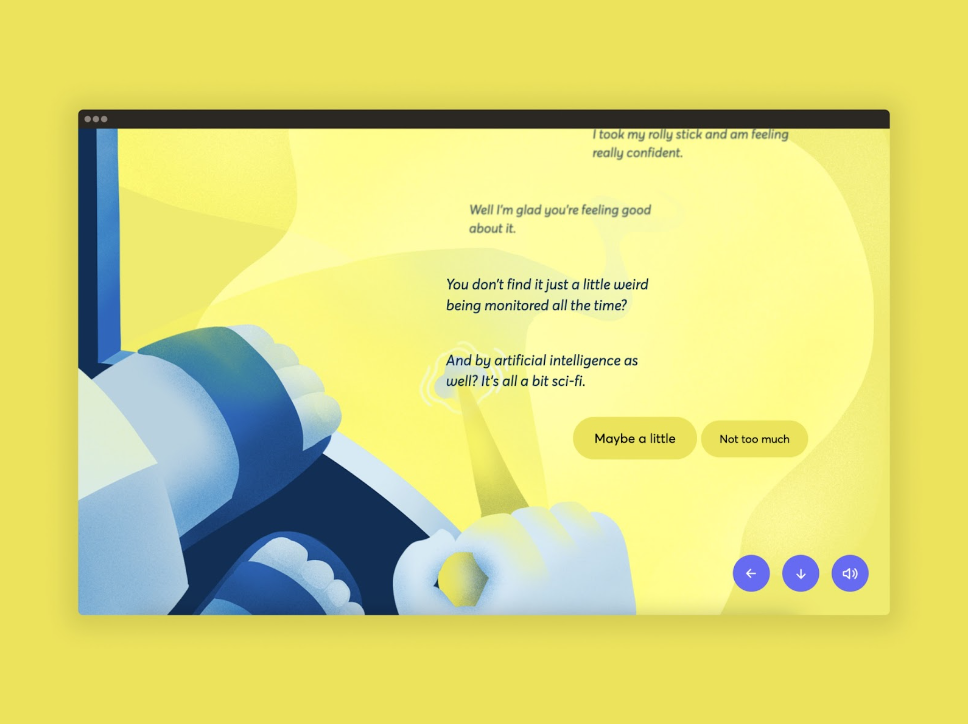

Force a decision. It’s easy to look at the future and move on. I like to force someone to make a choice. In one project, Eva Oosterlaken and I were tasked with communicating Scottish citizens’ hopes and fears for their health and care data to the Scottish Government. For each data relationship, we made a digital ‘choose your own adventure’ experience, where participants played through a conversation, and decided how they wanted to respond. We also role-played these characters with the digital design team, helping them feel their way into the worlds of the people they are designing for.

What formats do decision-makers pick up? I like to retell a story from Peter Singer about his book Ghost Fleet. The Australian national security trends report wasn’t getting read (because, in short, it was long and dull.) So Peter Singer refashioned it into a novel thriller about the future of war. This version has now been read by the NATO commander, a handful of 4S star generals in the US military and many others. What could be more immersive than a good novel? And what do you prefer to read on a long flight—a work-themed novel or a stack of briefing papers?

Get officials into dialogue with new voices. In SOIF’s collaboration with BOND, young people presented their own futures artefacts and challenged development sector specialists to respond. This brought fresh perspectives. At the Dutch Design Week, 30 civil servants are manning the exhibit. A critical outcome, as I see it, is for a range of civil servants to taste the rich insights that are emerging from the experience. This builds both belief in and excitement around the value of stepping into futures.

Get in touch if you’d like to speak to us about designing a participatory exercise.