How do you avoid being surprised by technological change? SOIF was asked this question recently by a British government department. The prompt for them was the emergence of the Chinese AI Deepseek—although they were hardly the only people to be surprised by that.

It can be hard to track technological change. This isn’t helped by some familiar tropes about technologies, such as the idea that “technological change is speeding up”, originally promoted by IBM to sell their consulting services.

And it turns out that this is one of those areas where some theory helps—as well as some grounded practice.

Brian Arthur’s book The Nature of Technology—regarded as something of a classic now—is a good starting point. He argued that technology is combinatorial, meaning that step changes come when different elements are combined in novel ways. This suggests that technology innovation often happens at intersections of disciplines, and that innovation is a complex emergent environment.

Frank Geels’ widely used ‘multi-level perspective’ model argues, more sociologically, that innovation emerges from niches that are able to try out new technologies which might have particular benefits for their business model. (Think of the bus companies that have introduced hydrogen buses.)

Sometimes these break out and disrupt that dominant technology system (“the regime”), sometimes not. If these are edge behaviours by organisations, we can also look for edge behaviours by other users. In The Signals Are Talking Amy Webb says that watching the way that people repurpose technologies to different ends produces clues. They hack things to change their use, they subvert rules or regulations, there are signs of different social values emerging.

Straightforward questions

And one of the classics is also worth looking at again. Many innovations fail, and Everett Rogers’ book The Diffusion of Innovation has a useful checklist of why this might be. Five factors account for 50% of the take up of an innovation, in both B2B and B2C markets: Relative advantage (compared to what the user currently does); Compatibility (with existing behaviours); Complexity of use—better thought of as ‘how simple is it to use’; Trialability (can people try it out); and Observability (are other people doing this, or is it just me?). Running through this list might have tempered some of the excitable coverage of the launch of Apple’s Vision Pro VR headsets last year.

There are also straightforward questions you can ask to understand the likely speed of take-up of a technology: does new infrastructure need to be built out? Do people or organisations need to buy new equipment? Do they need to learn new behaviours to use it? And so on. The broader social, economic and regulatory contexts always matter when thinking about technology.

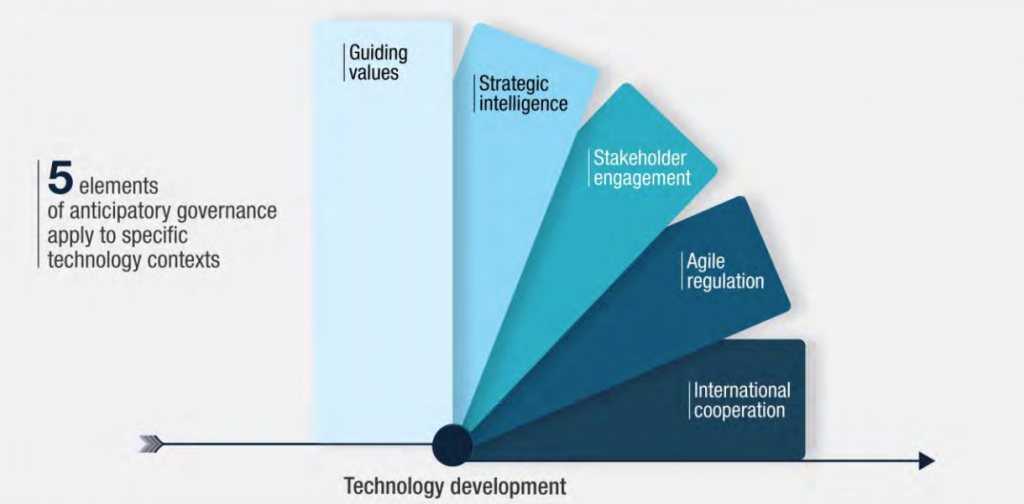

All of this means that good scanning and sense-making tools will get you quite a long way. At SOIF, we are fans of the OECD’s Framework for Anticipatory Governance of Emerging Technologies, published last year. It includes a helpful checklist of six sets of questions to ask when appraising a technology.

As for Deepseek, the reason it took people by surprise seems to have been Silicon Valley’s sense of exceptionalism and a belief, perhaps nurtured by venture capitalists, that new AI models cost hundreds of millions of dollars to develop.

And a bit more: that people generally underestimate the sophistication of China’s innovation system. As David Mindell writes in The New Lunar Society, “China has succeeded… because it has built up an ecosystem that links product innovation with process innovation.” The biggest source of surprise, when scanning, is always those untested assumptions about the world that create blindspots.

To discuss SOIF’s work on emerging technologies, please contact Andrew Curry, Director of Futures, or Peter Glenday, Director of Research and Programmes.